Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

THE GAWAIN POET'S LANDSCAPES

To contact us by email click the button

Poet and poem landscapes

The Gawain poet’s use of certain terms to describe landscape, an interest in hydrology, and a suggested connection to Dieulacres abbey, indicate that the author was most likely a clerk of a Cistercian abbey.

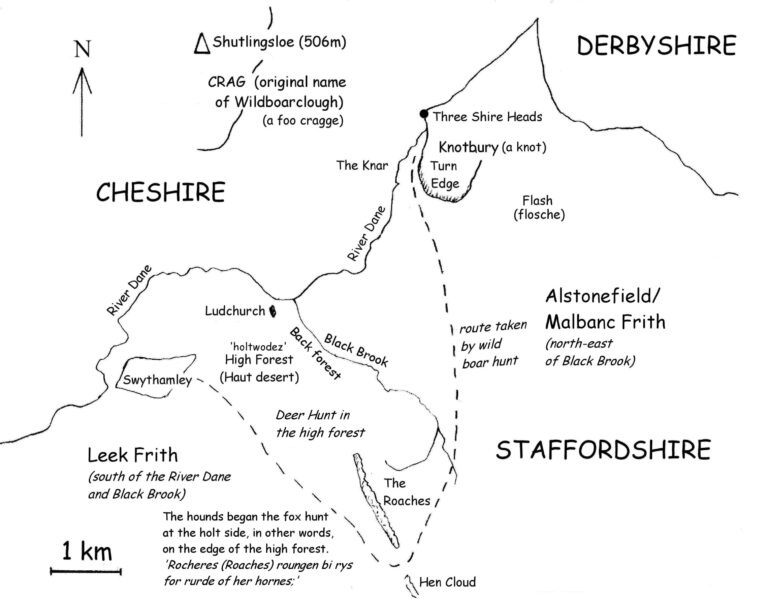

The poem was written in the dialect of an area where north Staffordshire meets the borders of Cheshire and Derbyshire, according to Angus McIntosh, language scholar. This area is known as “THREE SHIRE HEADS, the Three Sheres 1533, the (three) shire stones c. 1620, The Three Shire Mears 1656., “the three county-boundary stones”, where Cheshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire meet, v. ϸrēo, scīr, hēafod, stān, (ge)mǣre”. See English Place-Name Elements Relating to Boundaries by Boel Jepson.

Ralph W. V. Elliott, Leeds Studies in English, believes there are topographical references to local place names within the poem, Roaches, Flash, Kerre, Knot(bury) and Knar, these places are all in the Cheshire/Staffordshire Peak District.

The following information, concerning the poet and his landscapes, is based on Angus McIntosh and Ralph W.V. Elliott’s dialect and topographical references to the three shires border area of Cheshire, Derbyshire & Staffordshire in the English Peak District.

‘If von Schlieman could find the site of Troy with only Homer as his guide………’ J. Chadwick, (Hagiographer & scholar of ancient Northern European languages) his thoughts as he searched for the Green Chapel using the Gawain poem as his guide.

geography

The Cheshire side of the border was in the Manor of Macclesfield, the Keeper of Macclesfield forest was Sir John Chandos. The Staffordshire side of the border was in Leekfrith, a private forest, which once belonged to Dieulacres abbey. The area around Flash and Knotbury, where it seems the Boar was hunted, would have been in Alstonefield Frith, Lord of these lands in the late 14th century was Sir James Audley of Heighley.

Macclesfield Forest, in Cheshire, originally included Leek and Alstonefield Friths, both once known as Malbanc Frith, see English Heritage – Peak District By John Barnatt & Ken Smith -1997. Malbanc Frith was a private forest originally given to William de Malbanc by his cousin the Earl of Chester, Hugh Lupus. William’s son, Hugh de Malbanc, founded Combermere abbey in 1133, of which Dieulacres was a filial dependancy, a daughter-house.

The abbot of Dieulacres had purlieus/hunting areas, within the forest of Leek Frith. The abbot, was allowed to hunt with his own servants for no more than three days a week in his own woods in a purlieu.

Topographical names in the Gawain poem from the Boar Hunt

Bitwene a flosche in þat fryth and a foo cragge;

In a knot bi a clyffe, at þe kerre syde,

Þer as þe rogh rocher vnrydely watz fallen,

Þay ferden to þe fyndyng, and frekez hem after;

Þay vmbekesten þe knarre and þe knot boþe,

Place names and landscape suggested in the above text:-

Bitwene a flosche (Flash) in þat fryth (Alstonefield Frith) and a foo cragge; (Wildboarclough/Shutlingsloe)

In a knot (Knotbury) bi a clyffe (Turn edge), at þe kerre syde,

Þer as þe rogh rocher vnrydely watz fallen,

Þay ferden to þe fyndyng, and frekez hem after;

Þay vmbekesten þe knarre (the Knar) and þe knot (Knotbury) boþe,

Modern English Translation:- Between a pool in that wood and a forbidding crag. In the middle of a wooded mound beside a cliff at the side of the marsh, where the rough hillside had fallen in confusion, the hounds went to the dislodgement, with the men after them. The men cast about both the crag and the wooded knoll,

Explanation of names:-

Frith (a) Leekfrith parish is a few miles north of Leek and includes the Roaches. Frith is a Saxon term signifying a woody vale, lying between two hills, and such this was till the monks destroyed the wood, and improved the land by erecting three granges; New Grange, Roch and Swythamley. – From the History of the ancient parish of Leek in Staffordshire By John Sleigh.

Frith (b) enclosure, forest, wood, also in the sense of enclosed land, enclosure, park for hunting, forest, wood, cf. Old English friðgeard, ‘an enclosed space, lit. ‘peace-yard’ or ‘safety yard’, and Middle Swedish fridgiärd, an enclosure for animals; private forest [used locally, e.g. in Derbyshire, Duffield Frith]; very old [imported] Celtic word for forest. – From, Forests and Chases in England and Wales, c. 1000 to c. 1850 A Glossary of Terms and Definitions.

Frith (c) fyrhth(e), ‘land overgrown with brushwood, scrubland on the edge of forest’ (adjective gefyrhth sometimes found in charter boundaries), most frequently in modern forms as Frith and Thrift. The meaning explains the word’s adoption into Welsh, where in the fourteenth century ffridd meant ‘barren land’ (Gelling and Cole, p. 224). Modern Welsh fridd, plural friddoedd, is used of land at a certain altitude, above the belts of good arable. The mid-eleventh-century document known as Gospatric’s Wriot, which deals with land tenure in Cumberland, refers to rights on weald, on freyth, on heyninga: this could be translated ‘in forest, in heathland, in enclosed arable’ (Gelling and Cole, pp. 224-5; cf Duffield Frith 1332, earlier Forest/Chase, and Chapel en le Frith in Peak Forest).

Frith (d) & Flash Bitwene a flosche in þat fryth – If Flash* in the parish of Quarnford, is the poet’s ‘flosche’ in that frith, ‘þat fryth’ must have been Alstonefield Frith – The townships of Fawfieldhead, Heathylee, Hollinsclough, and Quarnford lay in what was called the forest of Alstonefield in 1227. The forest was known variously as the forest of Mauban and Malbank Frith by the early 14th century. From: ‘Alstonefield: Introduction’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 7: Leek and the Moorlands (1996). Alstonefield Frith was on the north-east border of Leek Frith, Black Brook being the boundary between Leekfrith and Alstonefield. Both ‘Alstonefield Frith’ and ‘Leek Frith’ were once part of the Forest of Macclesfield, until given to the Malbancs by the Earl of Chester, see – Peak District: Northern and Western Moors By Roly Smith, Andrew Bibby.

Quarnford was farmed by the Black Prince, it appears though that Sir James Audley was lord and receiver (of rents) in Quarnford. Quarnford township was held by Hugh Despencer, until his execution in 1326. In 1327 Quarnford was assigned to Sir Roger Swynnerton, along with Despenser’s share of Alstonefield manor and his manor of Rushton Spencer. In 1338, Sir Roger was stated to hold what was described merely as pasture on the moors in Quarnford, for which he paid a chief rent (an annual sum payable on some freehold property to the original freeholder) of two arrows a year to James, Lord Audley, lord of Aenora Malbank’s share of Alstonefield. From: ‘Alstonefield: Quarnford’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 7: Leek and the Moorlands (1996), pp. 49-56. URL: Alstonefield: Quarnford

* We know from the Alstonefield Registers that “Le Flashe” was a recognized settlement by 1538.

Flash/’Flosche’ – a pool or swamp – could be a reference to what is now called ‘Panniers Pool’, a packhorse crossing at Three Shire Heads. ‘Flosche’ however, was most probably a reference to the one time badly drained marsh/swamp area of ‘Flash’ village itself.

kerre, knot – The poet’s Kerre is derived from kjarr according to, ‘The Alliterative Revival’ By Thorlac Turville-Petre, as follows: The boar hunt is one of the most dramatic scenes of the poem. The boar is first tracked down ‘In a knot bi a clyffe, at þe kerre syde’,(1431). kerre/Ker/kjarr/carr, ‘a marshy thicket’, is a frequent place-name element in the Danelaw; also land which is badly drained and prone to flooding, often colonised by alder. Knot, ‘hillock’, is found in place- names in the north-west, but its only literary use as a topographical term is in Gawain. The place the poet must be referring to is now called Knotbury.

cragge – Crag – Steep rugged rock or peak. Wildboarclough was originally known as ‘Crag’ probably a reference to the steep-sided, 506m peak of Shutlingsloe with its conical Gritstone summit, see Peak District: Northern and Western Moors By Roly Smith, Andrew Bibby.

Wildboarclough township was described as “a bold mountainous district” by Samuel Bagshaw in 1850.

The Georgian mills at Wildboarclough were called Crag Mills, there is also a Crag Hall and a Crag Inn at Wildboarclough, all recalling the original name of this place. It has also been suggested that the “clough” of Wildboarclough, was derived from the Saxon term “clod”, a hill or rock, Wildboarclough would then be interpreted as “Hill of the Wild Boar”. Cloughs are usually however deep valleys, but this deep valley was once named after its surrounding crags, perhaps more specifically Shutlingsloe so “clod” or cloud, meaning hill, is not improbable.

Exactly between Wildboarclough/Crag and Flash lies Knotbury and Knar and the thorny hillside of Turn Edge (see below), as the poem describes, these were “Bitwene a flosche in þat fryth and a foo cragge;”.

Ralph W. V. Elliott, ‘Hills and Valleys in the Gawain Country’: In the parish of Wildboarclough at the heart of the real Gawain country the word “crag” occurs in several names, and only a short walk to the south is an example of an almost horizontally projecting crag, the Hanging Stone near Swythamley Park in the North Staffordshire moorlands, such as could aptly be described in the Gawain-poet’s words as “a foo cragge” (Gaw 1430).

It is intersting that R.W.V. Elliott notes that in the parish of Wildboarclough the word “crag” occurs in several names without mentioning that it was once the name of this place, he was perhaps not aware of this? The Hanging Stone near Swythamley Park, is too far south, Knotbury and Knar can only loosely be considered as being located between Hanging stone and Flash. Also, the poet does not consider the crag as just a ‘crag’ but a ‘forbidding crag’, perhaps indicating something larger and more imposing, than the Hanging stone.

“a foo cragge” foo – forbidding, also wicked – The poems of the Pearl manuscript, edited by Andrew and Waldron.

“There is a strong oral tradition that Shutlingsloe and nearby Wildboarclough were notorious centres of Witchcraft. Folk lore also claims that both were places where ancient cults were perpetuated.” – A Year of Walks in Cheshire By Clive Price. If Clive Price’s Folk lore and oral traditions are correct, “foo” meaning wicked, may have been a suitable description for the area once named ‘Crag’.

clyffe – cliff, ridge, hillside – same meaning for edge.

In a knot bi a clyffe, at þe kerre syde,

Þer as þe rogh rocher vnrydely watz fallen,

‘In a knot (Knotbury) by a cliff (Turn Edge) at the Carr side, there as the rough rocks unreadily were fallen,’ (where the rough hillside had fallen in confusion (unexpectedly)). Was the dislodgment of the rocks at Turn Edge, the place mentioned in the Gawain poem, where the men and the hounds gathered before searching out the boar between the knar and the knot? These fallen rocks are just over half a mile from Knotbury and less than a mile from Knar, they are dotted around the hillside of Turn Edge. at þe kerre syde – The River Dane runs along the west side of Turn Edge, there is also a brook to the east, between Wolf Edge and Turn Edge and also a Spring Head to the south. Turn Edge is surrounded by water of some description. Before better drainage, this must have been the marshy moorland that Flash village, a quarter of a mile away, took its name.

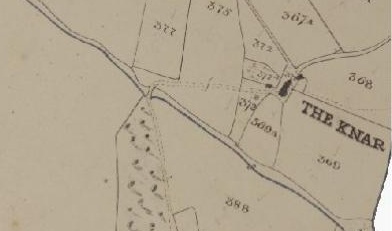

knar – a place just west of Knotbury on the Cheshire side of the River Dane. The poet called this place, þe knarre “the knar” which it was still referred to on the tythe maps of Cheshire in 1849.

The thorny hillsides between the Knar and the Knot, the land of the boar

Turn Edge, is a hillside once covered in thorn bushes, it was perfect boar country. “Vncoupled among þo þornez”, the hounds in the Gawain poem, were uncoupled/unleashed among the thorns to hunt the boar. The geology of Turn Edge with its fallen rocks, ‘rough rocks unreadily were fallen’ (near Wicken walls) described as a rock strewn uphill gully, could hardly have changed since the 14th century, if you ignore track marks made by trial bikes, indeed most of the poet’s hard landscape would be much as it was over 600 years ago.

The ‘Turn’ of Turn Edge, is a reference to the thorn bushes that once covered the hillside. The entry at the Middle English Dictionary gives the following on ‘þorn’: thorn (n.) Also thorne, thorun, thorowun, thurn(e, throrn, thron, turn.

In a knot bi a clyffe, at þe kerre syde, Þer as þe rogh rocher vnrydely watz fallen,

‘In a knot (Knotbury) by a cliff (Turn Edge) at the Carr side, there as the rough rocks unreadily were fallen,’ (where the rough hillside had fallen in confusion (unexpectedly)). Was the dislodgment of the rocks at Turn Edge, the place mentioned in the Gawain poem, where the men and the hounds gathered before searching out the boar between the knar and the knot? These fallen rocks are just over half a mile from Knotbury and less than a mile from Knar, they are dotted around the hillside of Turn Edge. at þe kerre syde – The River Dane runs along the west side of Turn Edge, there is also a brook to the east, between Wolf Edge and Turn Edge and also a Spring Head to the south. Turn Edge is surrounded by water of some description. Before better drainage, this must have been the marshy moorland that Flash village, a quarter of a mile away, took its name.

Mark Richards in his book, White Peak Walks, says the name Turn Edge means ‘thorn-covered hillside’. Cut-thorn Hill stands next to Turn Edge and confirms that the area, between Knar and Knotbury, was once covered in thorn bushes, the habitat of the wild boar, as described by the Gawain poet.

British Wild Boar – Wild boar are primarily nocturnal animals irrespective of sex, age, or season, although they may be more diurnal in times of food shortage. The daytime is spent sleeping in areas of thick cover in day nests, which are saucer shaped depressions in the ground which may be lined with leaves. Wild boar often have one long rest period in dense cover, during the day, that can last more than 12 hours. A short period of grooming on awakening, followed by four to eight hours of feeding during the night. Nocturnal feeding may be interspersed with a short rest phase. The onset of the daily cycle of activity is related to the time of sunset.

The boar was hunted during the daytime, the time when it would normally be sleeping in “areas of thick cover in day nests”. The huntsmen knew that the thorny thickets would provide suitable thick cover for the wild boar’s daytime resting place. This was kindly confirmed for me by Dr Martin Goulding CBiol MIBiol, PhD , wild boar ecology – “A thorn thicket covered hillside would indeed be a perfect place for a wild boar’s day nest”.

The Bloodhounds would have been released into the thorns to find the wild boar by scent, once found the hunters would then ‘beat on the bushes, and bade him rise’.

The last known fully wild boar in England was supposedly killed by Sir Richard de Musgrave in 1396, on Wild Boar Fell, Yorkshire Dales (hence the name). The story is given some endorsement by the fact that when his tomb in Kirby Stephen church was opened in 1847, a six-inch tusk was found with the skeleton. (Helen Cooper)

However…..

From, ‘The sports and pastimes of the people of England’ By Joseph Strutt 1801 – References to wild boars might be almost indefinately extended, for they overran the whole country for many centuries, and were afterwards hunted in all the great forests of England. As forests lessened in extent the wild swine decreased in numbers, but there are abundant proofs of their thriving in Durham, Lancashire, Staffordshire, and Wiltshire in the sixteenth century. James I. hunted the wild boar at Windsor in 1617. They were still wild at Chartley, Staffordshire, in 1683. Charles II.’s reign is the latest time at which this animal is known to have been found in England in a really wild state. Various vain efforts were made to reintroduce them into England during the nineteenth century.

From the Gawain poem concerning the boar and the hounds: ‘Very often he stands at bay and causes injury in the midst of the pack of hounds. He hurts some of the hounds, and they howl and yell most miserably.’

The best account of the old English hunting of the wild boar is given in George Tuberville’s liberally illustrated “Noble Art of Venerie or Hunting,” which was first printed in 1575 and reproduced in 1611. It is worth comparing SGGK and Turbeville’s account of hunting boar with hounds and the damage done to them by the boar, also the killing of the boar with a sword. The slaying of the boar in this manner wasn’t necessarily to show Bertilak’s prowess as a hunter, Turberville tells us that the ‘sword’ or the ‘boar-spear’ are the proper weapons used to hunt and kill a wild boar.

Ralph W. V. Elliott, ‘Hills and Valleys in the Gawain Country’: In the parish of Wildboarclough at the heart of the real Gawain country the word “crag” occurs in several names, and only a short walk to the south is an example of an almost horizontally projecting crag, the Hanging Stone near Swythamley Park in the North Staffordshire moorlands, such as could aptly be described in the Gawain-poet’s words as “a foo cragge” (Gaw 1430).

It is intersting that R.W.V. Elliott notes that in the parish of Wildboarclough the word “crag” occurs in several names without mentioning that it was once the name of this place, he was perhaps not aware of this? The Hanging Stone near Swythamley Park, is too far south, Knotbury and Knar can only loosely be considered as being located between Hanging stone and Flash. Also, the poet does not consider the crag as just a ‘crag’ but a ‘forbidding crag’, perhaps indicating something larger and more imposing, than the Hanging stone.

“a foo cragge” foo – forbidding, also wicked – The poems of the Pearl manuscript, edited by Andrew and Waldron.

“There is a strong oral tradition that Shutlingsloe and nearby Wildboarclough were notorious centres of Witchcraft. Folk lore also claims that both were places where ancient cults were perpetuated.” – A Year of Walks in Cheshire By Clive Price. If Clive Price’s Folk lore and oral traditions are correct, “foo” meaning wicked, may have been a suitable description for the area once named ‘Crag’.

Hugh de Malbanc – founder of Combermere Abbey, held Wistaston near Crewe, was Lord/Baron of Alstonefield, Staffordshire, and Nantwich, Cheshire. Hugh owned salt-pits in Wych/Nantwich, once called Wich-Malbanc after the Norman Malbanc family who were originally, of Brescy/Bressy/Brassey near Caen, Normandy. Dieulacres Abbey owned Salt-pits in Middlewich and Nantwich. In 1133 a fourth part of Wich-Malbanc was granted by Hugh Malbank to the abbot and convent of Combermere.

A HISTORY OF THE TOWN AND PARISH OF NANTWICH. OR WICH-MALBANK IN THE COUNTY PALATINE OF CHESTER. BY JAMES HALL, WILLASTON, NANTWICH. Towards the end of the eleventh century, a religious revival broke out, chiefly through the zealous preaching of Cistercian monks, who were welcomed to England by high and low. Hence the Norman Barons of Wich-Malbank, impressed with the new ideas of these reformers, made grants of land, salt-houses, &c., for the erection and maintenance of Abbeys and Convents for this order, thus providing better religious teaching in one of the “dark places of the earth;” and very probably William Malbedeng built the first Chapel of Nantwich, which is mentioned in his son’s Charter, dated c. 1130.

The above suggests that the new order of Cistercian monks would have also been welcome “in þat fryth”, specifically Alstonefield Frith, once owned by the Malbancs.

When Hugh de Malbanc founded Combermere abbey (Ches.) in 1133, he included half the vill of Alstonefield among its endowments, perhaps the estate which became Gateham grange. From: ‘Alstonefield: Alstonefield’, A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 7: Leek and the Moorlands (1996), pp. 8-27.

Rake – And ryde me doun þis ilk rake bi ȝon rokke syde, Til þou be broȝt to þe boþem of þe brem valay;

There is a rake/track heading towards Knotbury and Flash (flosche), the highest village in England. Hollinsclough, only 3 miles from Flash/’Flosche’ in Gawain poet country, has in fact three rakes, the other two smaller rakes, Limer and Swan, are old packhorse routes, taking the names of local families. In Hollinsclough we have tracks still called ‘rakes’, and a marshy thicket ‘Moss Carr’, ‘kerre’,

Hautdesert – French, ‘haut’ means high, and ‘desert’ and ‘wilderness’ were alternative terms for the wild uncultivated forest. Hautdesert is literally High forest. F. W. M. Vera in the book, Grazing Ecology and Forest History, explains that ‘Wilderness’ was originally a term used to mean the closed forest, later it would mean any area of land under forest law. The closed forest meant the closed canopy of a dense, usually Oak, high forest, just as Hautdesert is described in the Gawain poem, a forest full deep with many trees for two miles with huge trunks. The description of the demesne of Hautdesert is of a high forest grown for its timber and for the protection of its deer. See more in section: ‘Desert-forest’.

The Roaches (French, les roches) – The Rocks

And ruȝe knokled knarrez with knorned stonez; Þe skwez of þe scowtes skayned hym þoȝt.

translation – And rough, lumpy crags with rugged outcrops; the clouds seemed to him to be grazed by the jutting rocks.

The above description, as Gawain searched for the green chapel, is very similar to a description of the Roaches in Sleigh’s History of Leek, published 1883. Sleigh writes of Robert Plot’s observations in the seventeenth century: Plot, in his somewhat exaggerated style, jots down – “When I came to Leeke and saw the Hen-cloud, and Leek-roches (some of them kissing the clouds with their tops and running along in mountainous ridges for some miles together), my admiration was still heightened to see such vast rocks and such really stupendous prospects, which I had never seen before, or could have believed to be anywhere but in picture.”

Plot’s, description of the clouds kissing the tops of the rocks/roches, is very similar to the Gawain poets, clouds being grazed by jutting rocks, also thought to be a description of the Roaches.

‘Þenne such a glauer ande glam of gedered rachchez

Ros, þat þe rocherez rungen aboute;’

The above “rocherez” is also believed to be a reference to the Roaches, where the boar hunt crossed and then headed northwards towards Flash, Knotbury and Knar.